Voter registration modernization guide

Voter registration modernizations like updated Motor Voter programs, electronic transfer of voter registration data from the Department of Motor Vehicles, and automatic voter registration (AVR) are popular new ways of registering voters in America.

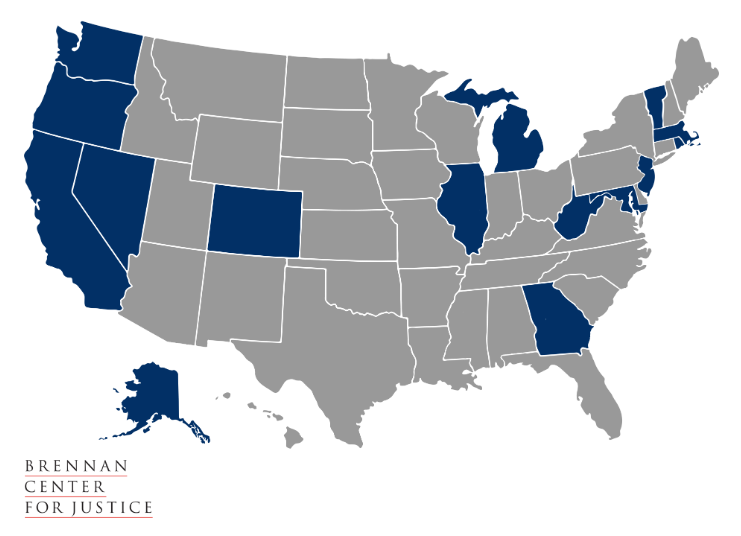

According the the National Conference of State Legislatures, 17 states and the District of Columbia have approved AVR as of April 2019. Using slightly different criteria, the Brennan Center for Justice counts 15 states with AVR.

Like many updates in election administration, decisions are made by state government leaders and then rolled out to local election offices for implementation. In order to achieve the desired results of voter registration modernization policies, it’s critical that local election officials are equipped with field-tested best practices.

This tool provides local election officials with background on voter registration modernizations as well as insights and lessons learned from across the country.

You can read more about how information was gathered for this tool on the Center for Technology and Civic Life’s website.

Like many government services, voter registration has been streamlined in recent years. Advances in technology are helping to make registering voters faster, simpler, more convenient, and less expensive – all while helping to include more eligible citizens and improve the accuracy of voter records.

These new methods to streamline voter registration go by many names – including automatic voter registration and voter registration modernization – but what they all have in common is to make it easier for both voters and election officials to keep registration data current.

Election officials review ideas regarding voter registration modernization at the workshop in Chicago in May 2018

Modernized registration works by automating one or more steps in the process. For instance, with electronic transfer, the movement of data from one office to another is automated, eliminating paper forms and reducing inaccuracies. And by shifting from an opt-in to an opt-out approach, the process smoothly integrates voter registration into an existing, familiar interaction for the voter.

What is voter registration modernization?

Voter registration modernization policies like Automatic Voter Registration (AVR) are updated versions of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA), commonly referred to as “Motor Voter.”

One of the requirements of Section 5 of the NVRA calls for states to offer eligible citizens the opportunity to register to vote when they apply for or renew their driver’s license at the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). Voter registration modernization policies update this requirement by automatically registering eligible citizens when they apply for or renew their driver’s license. The citizen is offered an opportunity to opt out if they choose not to register.

Section 7 of the NVRA requires other agencies besides the DMV to offer voter registration services. These include public assistance agencies like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Medicaid program, offices providing services to people with disabilities, and Armed Forces recruitment offices. Each state has some leeway to designate which offices must provide voter registration opportunities to their clients. In addition, some states have included the Section 7 agencies in their modernization efforts to streamline the electronic transmission of voter registration data.

Not only are voter registration modernizations making the process more streamlined for voters, but the registration process is becoming more streamlined for election offices, too. Many states implementing AVR and similar policies are moving away from shuttling around paper forms to electronically transferring records between the government agencies and the election office, resulting in more timely updates to the voter registration database.

Opt-out versus opt-in

Research shows that more people register to vote when they have to opt out of registration rather than opt in to it.

For another example, consider organ donation. According to recent studies, in countries such as Austria, laws make organ donation the default option, and so people must explicitly opt out of organ donation. In these so-called opt-out countries, more than 90% of people choose to donate their organs. Yet, in countries such as the U.S. and Germany, people must explicitly opt in if they want to donate their organs. In these opt-in countries, fewer than 15% of people choose to donate their organs.

Opting out of organ donation frames the idea of being an organ donor as the norm or usual thing to do. AVR is based on the same principle: being a registered voter is the norm or usual thing to do.

The opportunity to opt out of voter registration also helps safeguard people with protected addresses like law enforcement officers, public figures, and other protected groups.

Different versions of Automatic Voter Registration

As of April 2019, 15 states and the District of Columbia have authorized automatic voter registration, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

There are currently 2 types of opt-out methods being used in the states:

- Opt out during the transaction at the DMV or other agency

- Opt out by replying via mail within a certain time period

In most states, the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) is currently the only agency to participate in new modernizations. However, some states also partner with other verified state agencies, like the health benefits exchange and department of social services.

States that have approved Automatic Voter Registration

Benefits of other voter registration modernizations

AVR is often in the headlines, but the term doesn’t capture other voter registration modernization efforts in the United States that have had similar outcomes.

Delaware, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Virginia are examples of states that updated their voter registration process to improve the transfer of voter registration data between government agencies.

Delaware

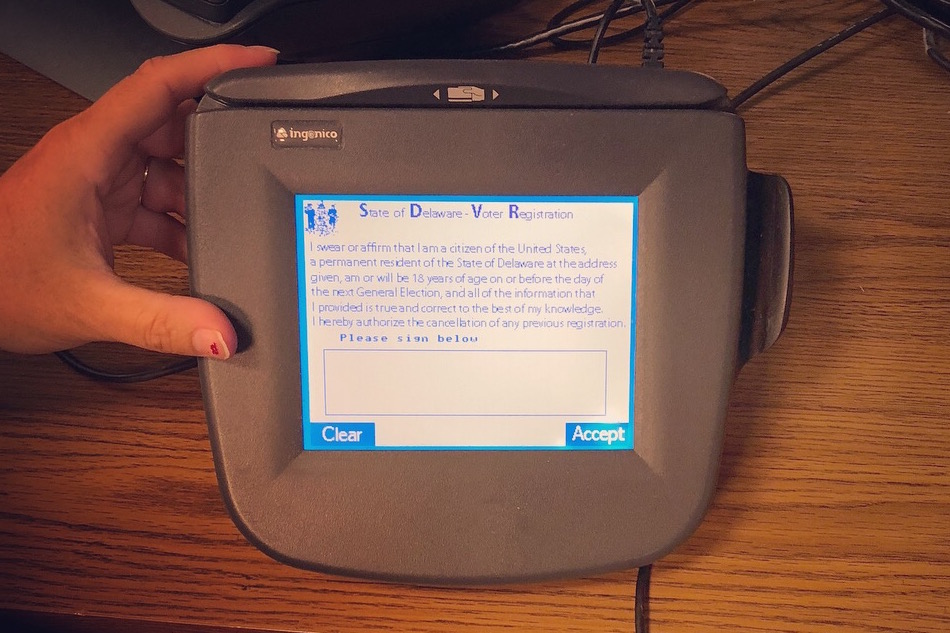

Delaware implemented eSig, or e-signature, at their DMVs in 2009.

When customers visit a Delaware DMV to renew or apply for a driver’s license, they are asked a series of questions about voter registration on an electronic signature pad. This interaction allows the DMV to electronically transfer collected voter registration data and signatures to the election office on a daily basis rather than deliver completed paper voter registration forms.

Delaware eSig pad prompts the reader to verify registration eligibility

And it’s not only a quick transfer of data from the DMV to the election office — it’s also a quick transaction for the DMV customer. The average transaction time for voter registration at the Delaware DMV is 15 seconds.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has had its own version of e-signature in place since approximately 2003.

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) sends an electronic file of voter registration and signature data to the Secretary of State’s (SOS) office three times each week.

In the last two years, a recent tech upgrade allowed the questions to be presented in 12 languages beyond English and Spanish.

Michigan

Michigan currently has a paper-based process for new voter registrations but incorporates important electronic elements.

For example, when a customer chooses to become a new registered voter during an SOS transaction, they are given a pre-populated paper registration form to complete and sign. As of 2000, Michigan state law requires an individual’s voter registration address to be the same as their driver’s license address.

This means that when an individual changes their address at a SOS branch office (or online) for their driver’s license, it automatically changes their address for their voter registration record and vice versa.

Virginia

Virginia adopted Delaware’s eSig and added additional features in 2016.

The most notable feature is a real-time connection between the DMV and the state election office. This connection allows the DMV system to determine a customer’s voter registration status during the DMV transaction and customize questions based on that status.

The upgrade not only transformed an inefficient, paper-driven voter registration process into an all-electronic one, but it also integrated the state’s online driver’s license transactions with the state’s online voter registration system.

Sources

U.S. Department of Justice: “The National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA)”

Brennan Center for Justice: “Automatic Voter Registration”

National Conference of State Legislatures: “Automatic Voter Registration”

Local election officials are accustomed to new legislation that impacts their operations. How might voter registration modernizations change how you and your team do your jobs?

Chuck Hollis and Norelys Consuegra share insights about Rhode Island’s voter registration modernization at the Chicago workshop

11 things you should know when rolling out voter registration modernization

- Your office’s relationship with the state election office is critical. Communicate with the state election office regularly about updates, policies that are working well, and areas for improvement with voter registration modernization.

- Your office’s relationship with the DMV is important. Understand the DMV service experience and agency goals. Recognize that simplifying the voter registration process can reduce DMV transaction times. Note: Your relationship with the DMV may be mediated through the state election office, but you should get to know your local DMV administrators.

- Your office’s work to review and verify digital voter records is ongoing. Voter registration modernization does not eliminate human oversight and intervention in the voter registration process.

- Your office may experience temporary shifts in workload. Surges of address changes from the DMV and learning a new review process requires minor staffing adjustments.

- Transmitting voter registration data electronically (rather than by paper) saves shipping costs, reduces data entry time, and prevents mistakes.

- Voter registration modernization isn’t perfect. Identify a way to roll back changes when you find out a mistake was made. Be prepared to troubleshoot data transfer issues between your office, the state voter registration database, and the DMV.

- Be aware of voters who may have different addresses with the DMV and the election office. For example, these can be your overseas voters.

- Much of the public already believes that their voter registration data is electronically transferred between state and local government agencies. Communication about your voter registration modernization with voters can be minimal.

- Voter registration modernization reduces lines and frustration on Election Day. More accurate voter rolls minimizes provisional ballots.

- How the voter registration questions are phrased and sequenced impacts the process. If you are able to review your state’s plans in advance, pay special attention to translations into languages other than English.

- Over time, local advocacy groups and campaigns will be able to spend fewer resources registering voters and more resources educating voters. However, as the new policy goes live, all stakeholders should be prepared for the usual challenges with an updated voter registration process

Frequently asked questions

Staffing for voter registration modernization

Q: How does voter registration modernization change the workflow in the local election office?

A: The core process of reviewing and approving or rejecting voter registration applications will remain the same. But the the way you receive these records will change. You can expect fewer paper voter registration records from the DMV. This means you’ll spend less time managing paper, typing in data, and doing data entry. However, you can expect more digital voter registration records in your queue from the DMV. This means you’ll spend more time reviewing and verifying records. Overall, you should anticipate more digital voter registration transactions that take less time to process than paper transactions.

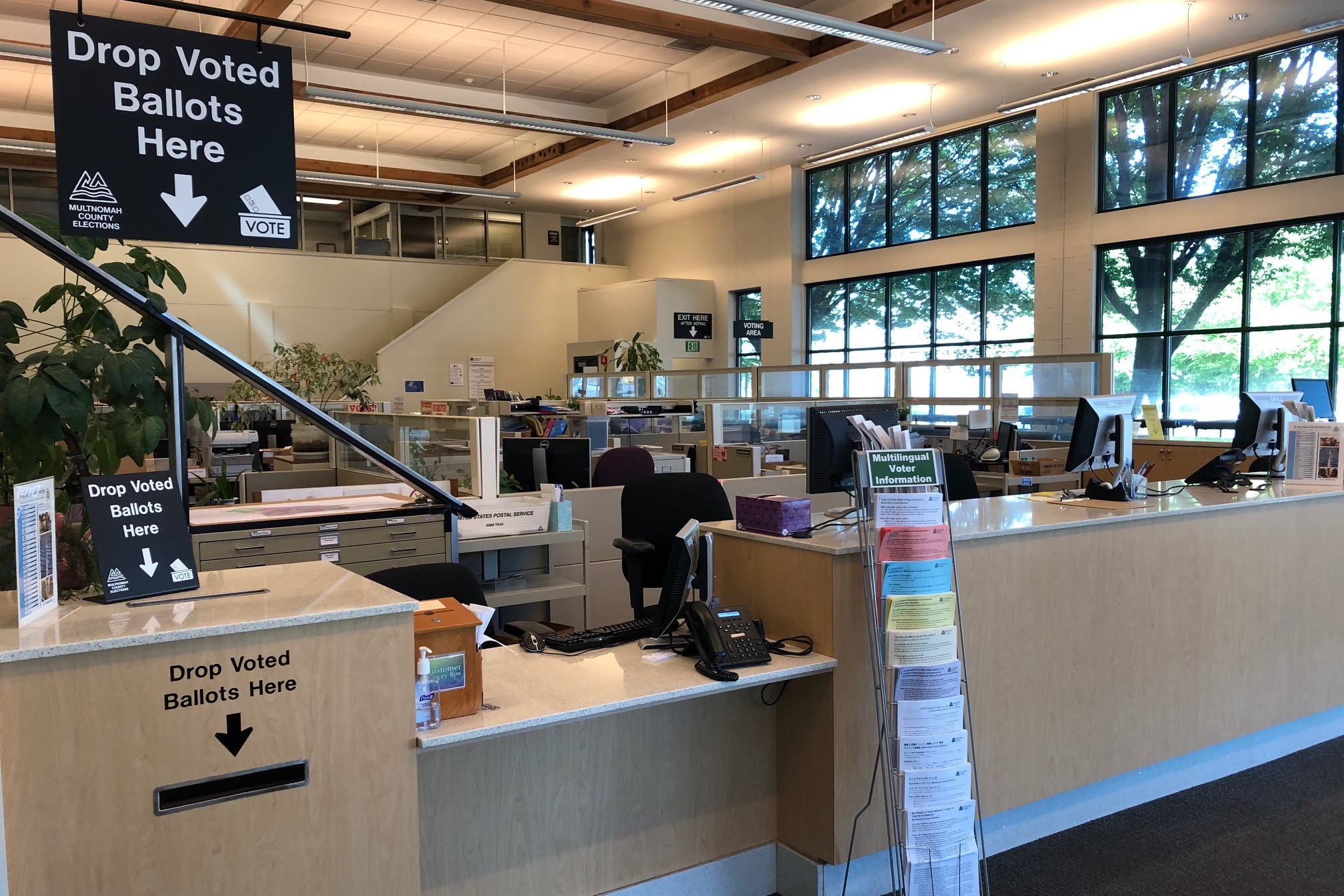

Voter service desk in Multnomah County, Oregon — one of the first states to adopt modernized voter registration

Q: Will I need to hire additional staff?

A: Staff members who process paper forms will spend less time with paper and more time reviewing and verifying digital voter registration records. Because of the efficiencies in reducing paper, you may not need to hire additional staff to process paper voter registration forms.

Other resource implications of voter registration modernization

Q: What technology is required?

A: Your state voter registration database must communicate with the DMV database. Signature pads or card readers must be in place at the DMV to capture voter signatures. Contact your state election office to learn more about the connections between your voter registration database and other government databases.

Q: How does voter registration modernization change how our office stores voter registration records?

A: Voter registration modernization means more voter registration data will be stored digitally. You should speak with your state election office to learn more about digital record storage of voter registration data. With this in mind, your office may require less physical space to store paper voter registration records.

Important government relationships for voter registration modernization

Q: How does voter registration modernization impact our office’s relationship with the state election office?

A: Your office should have a strong relationship with your state election office. This means they are sending you regular updates to the voter registration database and you are able to report issues and ask for help in a timely manner.

Q: How does voter registration modernization impact our office’s relationship with the DMV?

A: Your office should have a strong relationship with the local DMV offices. This means you are visiting their offices regularly to observe the voter registration process and answer questions. Your state election office will most likely manage the relationship with the state DMV office, but good relationships between local offices can help you identify and fix any problems easily.

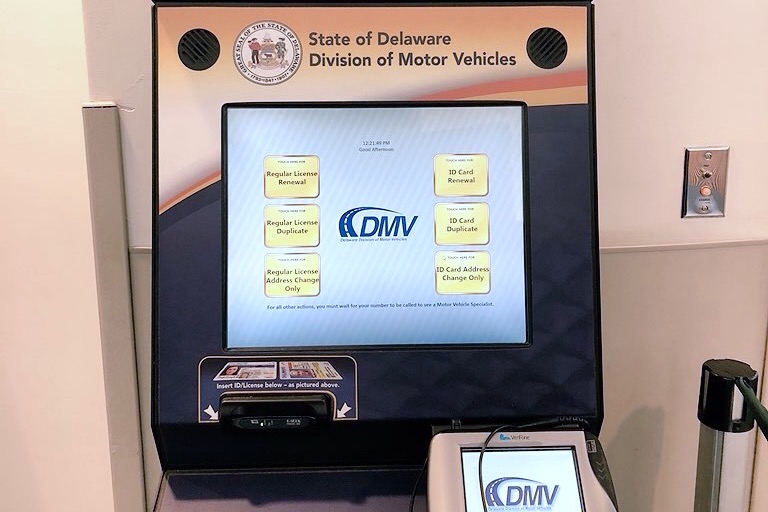

A DMV kiosk in Wilmington, Delaware

Communicating about voter registration modernization

Q: How should I talk about voter registration modernization with the public?

A: Keep in mind that voters may think the government is already transmitting voter registration information electronically, which means this new policy is meeting their expectations rather than exceeding them. Tell voters what’s changing for them (if anything) and avoid terms like “automatic” and “Motor Voter.” Phrases like “streamlining the DMV voter registration process” or “electronically transferring voter registration information” may make more sense.

Ben Schler and Amber McReynolds discuss Colorado’s voter registration modernization experience at the Chicago workshop

Q: What steps can I take to prepare answers to the public’s questions about voter registration modernization?

A: Communicate internally with your state election office and DMV office to understand how your new voter registration process works. By understanding how voter registration data is collected and transferred, you’ll be able to clearly explain the new process to the public. This can also help keep the communication consistent from the state election office, DMV, and local election office.

Q: How can I reassure the public that voter registration modernization is a trustworthy process?

A: Your confidence in and understanding of the updated voter registration process in important when communicating with the public. Let voters know that their data is securely transferred from the DMV to your voter registration database, where it is reviewed and verified by local election office staff. To educate your staff and community, consider adding a short description to your election website that explains how voter registration data is electronically transferred between government offices.

Want to dig deeper into best practices for voter registration modernization? Check out these useful resources.

Brennan Center for Justice: “AVR Impact on State Voter Registration”

Center for Civic Design: “Modernizing Voter Registration”

California Secretary of State: “California Motor Voter”

The Center for Technology and Civic Life and the Center for Civic Design wish to thank the election officials, experts, and advocates who contributed their insights to help us build this guide.

By participating in our Chicago workshop as well as interviews and site visits, they have played a central role in identifying the benefits and challenges of voter registration modernization.

- Kiyana Asemanfar, California Common Cause

- Norelys Consuegra, Rhode Island Department of State

- Edgardo Cortes, Virginia Department of Elections

- Lisa Danetz, Democracy Fund

- Josh Gross, Perry County, Illinois Clerk

- Chuck Hollis, Rhode Island Department of Motor Vehicles

- Kevin Keene, Harford County, Maryland Board of Elections

- Dale Livingston, Harford County, Maryland Board of Elections

- Elaine Manlove, Delaware Department of Elections

- Kyle Martel, Main Street Alliance of Vermont

- Amber McReynolds, Denver, Colorado Elections Division

- Sarah Mohan, Harford County, Maryland Board of Elections

- John Odum, Montpelier, Vermont City Clerk

- Noah Praetz, Cook County, Illinois Clerk

- Ben Schler, Colorado Secretary of State

- Tim Scott, Multnomah County, Oregon Elections Division

- Scott Seeborg, Center for Secure and Modern Elections

- Will Senning, Vermont Secretary of State

- Kirk Showalter, Richmond, Virginia General Registrar